Parking Lots and Protests: The Mallory House Incident in 1971

A shattered glass door. Insults exchanged such as “stooge,” “commie,” and “hooligan.”1 Punches thrown. This describes a scene in a parking lot on the edge of campus at George Mason College in 1971, which was then a branch college of the University of Virginia. A verbal then physical fight occurred between a male student and a male staff member. There were conflicting reports about who threw the first punch, but both sides agreed that the altercation began over a dispute about a parking permit.

In the 1970s United States, political conflicts and debates erupted across different college campus spaces—including parking lots. This essay details the Mallory House incident and analyzes the meanings behind the verbal insults exchanged. The built environment of college campuses, especially parking lots, can serve as a window into understanding broader political issues such as youth counterculture, debates over abortion rights, and university politics.

On Friday, December 3rd, 1971 around 8pm, Dani Devere, a Northern Virginia College student, parked near the Mallory House to pick up her friend Jack Cassedy, GMC student and editor of the student newspaper Broadside. The Mallory House included the offices of the Buildings and Grounds department, purchasing agencies, and the Broadside. James Conner, Superintendent of Buildings and Grounds, and William Clark, a purchasing agent of GMC, soon arrived to pick up papers in Conner’s office. Conner asked Devere why she did not have a parking permit. Clark claimed she replied “nast[ily]…none of your business,”2 while Devere claimed she was verbally harassed and smelled alcohol on his breath.3

Cassedy then met them outside and told Devere to call the police. A verbal then physical fight ensued between Cassedy and Conner, though there were conflicting accounts over specifics. Supposedly Cassedy said, “You two are stooges of the administration trying to close down the newspaper” and “made other incoherent remarks about abortions.”4 The two staff members allegedly insulted Cassedy’s long hair and called him a hippie, commie, and another offensive term that used a racial slur.

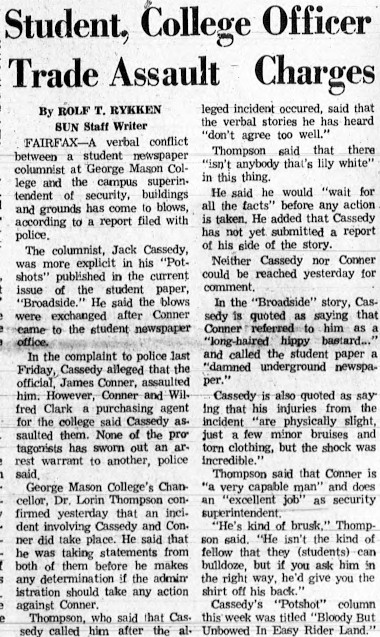

Figure 1. An article a week after the Mallory House incident was published in the local city newspaper Northern Virginia Sun. The Fairfax city police were called and reported the verbal and physical conflict in their files. Northern Virginia Sun, December 10, 1971.

Figure 2. James Conner pictured three months before the incident by an “out building.” This area, called “college property” since it was across from Ox Road west of campus, included the Mallory House, the residence of the Chancellor, the Police Chief Law’s home, and a vineyard. Broadside September 29, 1971, p.3

This event speaks to national trends of radical youth counterculture in the 1970s, mostly associated with protesting the Vietnam War, participating in the sex revolution, supporting the Black Panther movement, and questioning authority, especially on college campuses. The insults about Cassedy’s long “hippy hair” and his accusation of the “stooges” trying to shut down Broadside reflect broader political disagreements between students and staff. This was the same year that GMC faculty member James Shea caused controversy on campus over his protests against the Vietnam War. In short, the 1970s were contentious times in the U.S. when generational conflicts often played out on college campuses.

This event speaks to national trends of radical youth counterculture in the 1970s, mostly associated with protesting the Vietnam War, participating in the sex revolution, supporting the Black Panther movement, and questioning authority, especially on college campuses. The insults about Cassedy’s long “hippy hair” and his accusation of the “stooges” trying to shut down Broadside reflect broader political disagreements between students and staff. This was the same year that GMC faculty member James Shear caused controversy on campus over his protests against the Vietnam War. In short, the 1970s were contentious times in the U.S. when generational conflicts often played out on college campuses.

Among the verbal insults exchanged in front of the Mallory House that night were remarks related to national debates over abortion rights that had recently filled the pages of the Broadside. In 1973, the Supreme Court issued the federal right to abortion in the Roe v. Wade decision. Before abortion was legalized in 1971, however, Broadside published out of state abortion referrals for months. Despite backlash from the administration that they were directly violating the law, editors like Jack Cassedy continued to publish pro-abortion articles.

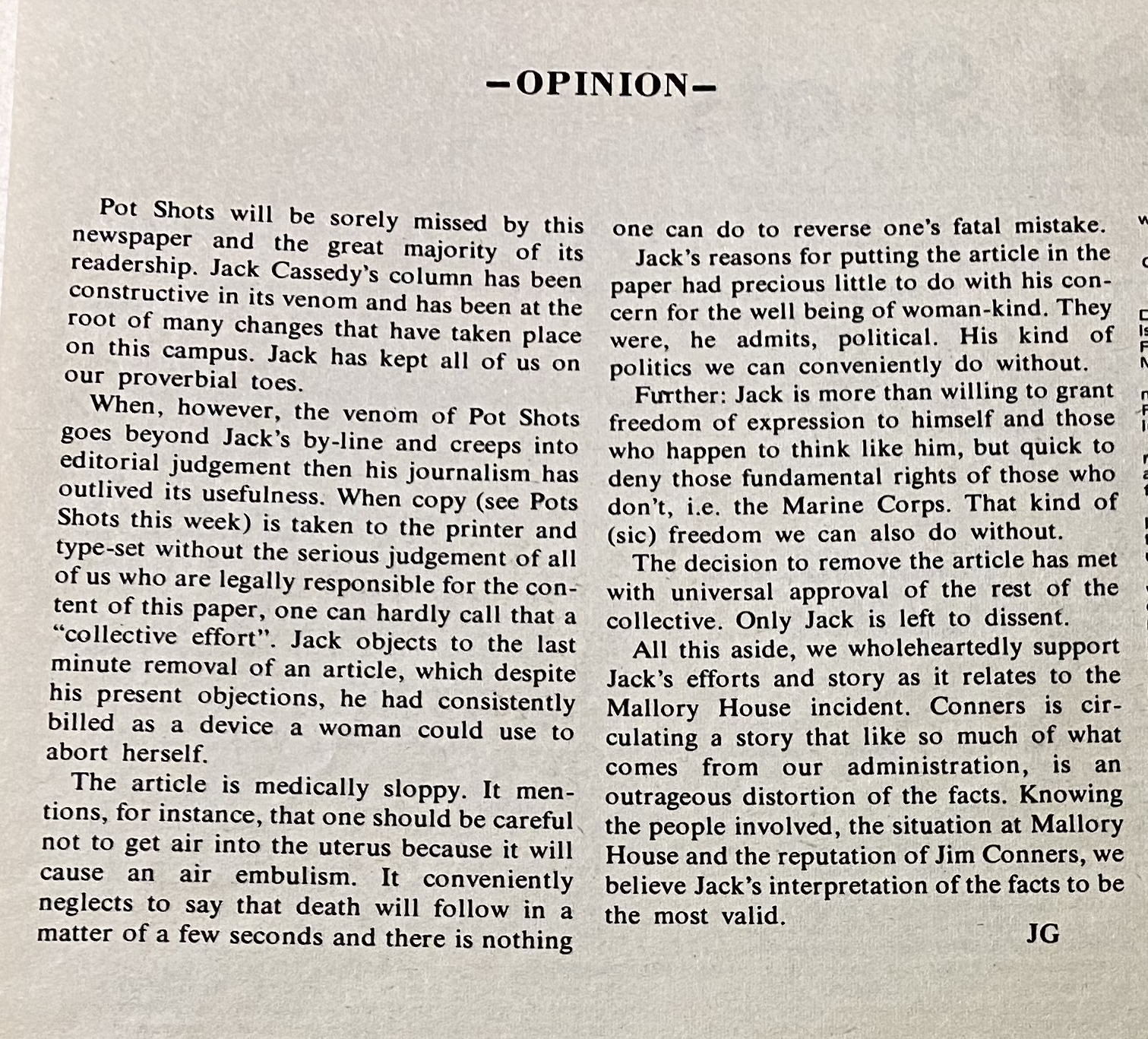

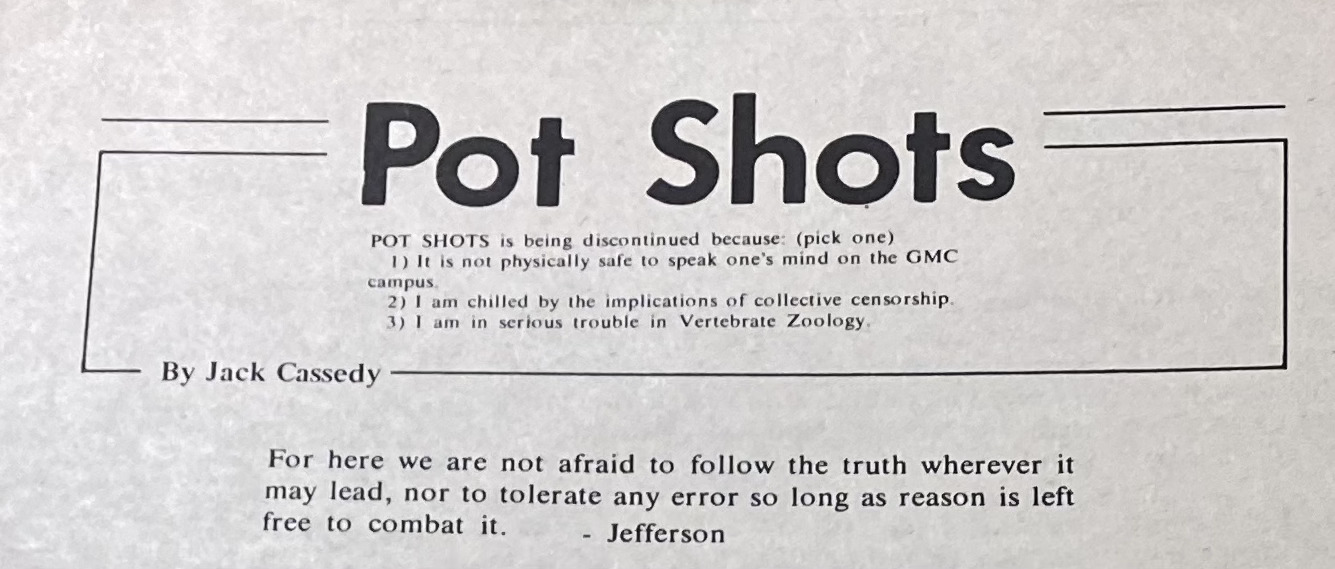

But one of Cassedy’s Broadside abortion articles was revoked, as the editors later stated it was unfactual and medically harmful. Later articles implied Cassedy’s column “Pot Shots” was removed altogether because of this “medically sloppy” article that had “little…concern for the well being of woman-kind.” Broadside editors made sure to express explicit support for Cassedy in regard to the Mallory House case but remained critical of this specific article. In this case, Cassedy’s political activism was negatively received by administration, staff, and students. This also suggests a pattern of pressure from the administration regarding content published in the student newspaper during this time.

Figure 3. Broadside article implying the removal of Cassedy’s column “Pot Shots” due to a previous “medically sloppy” article about abortion. Editors remained supportive of Cassedy in relation to the Mallory House incident, however. (Broadside December 13, 1971).

Figure 4. Cassedy acknowledging the discontinuation of his column “Pot Shots” due to an inaccurate article about abortion. The number #2 reason for the removal of his column is noteworthy: “I am chilled by the implications of collective censorship.” (Broadside December 13, 1971, p.4))

Figure 5. A cartoon most likely drawn by a student critical of Broadside. Though this was published three years after the Mallory House incident, some students remained critical of Broadside for political bias in printing the “news [they] deem fit to print.” (Broadside Photograph Collection, 1974-04-20).)

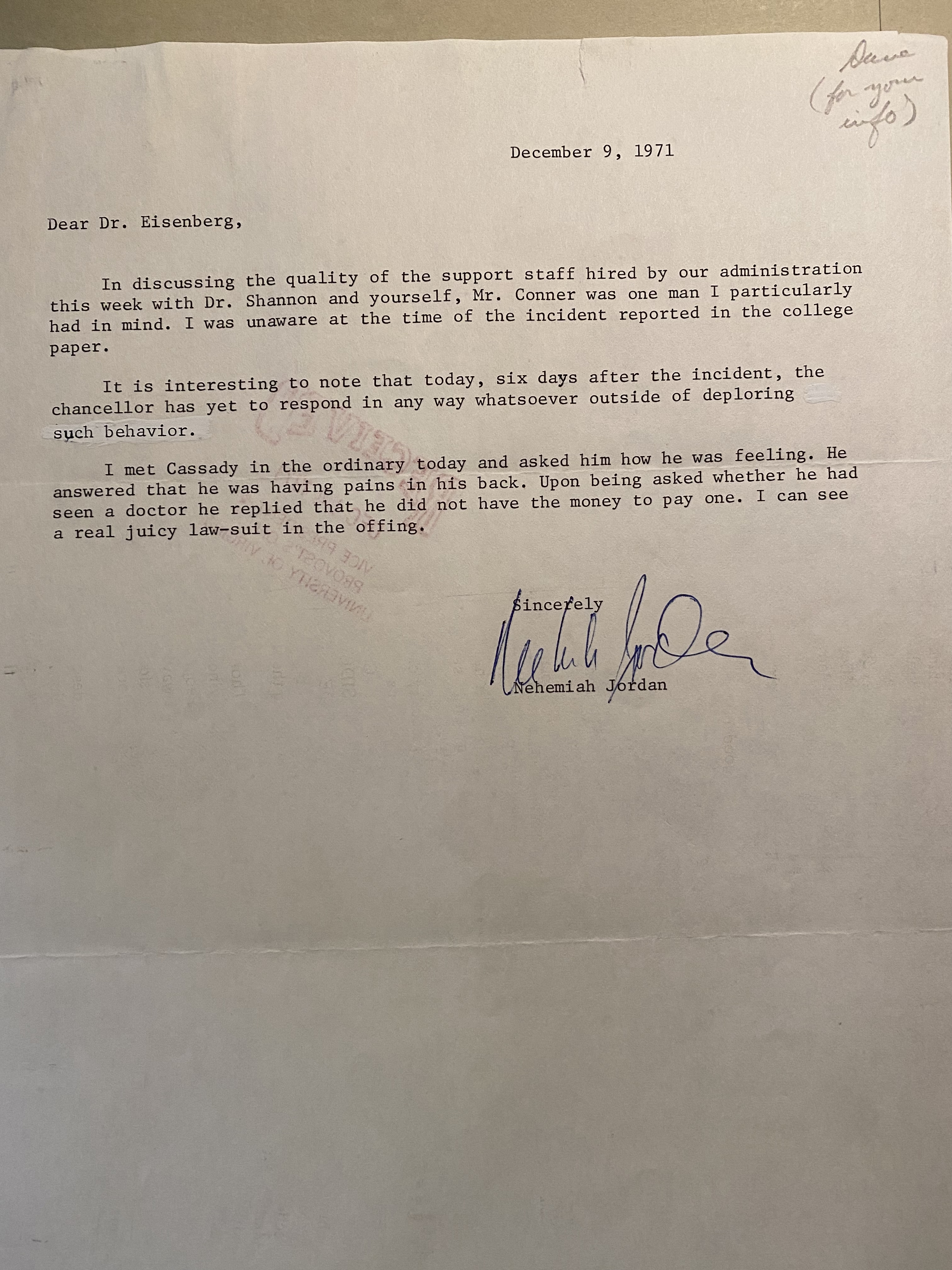

The Mallory House incident additionally sheds light on university politics of the time, especially between parent institutions and their branch colleges. In a letter six days after the conflict, Nehemiah Jordan, from UVA President Shannon’s office, pushed for GMC Chancellor Lorin Thompson to publicly respond to the incident. Jordan mentioned Broadside had already published an article, implying that this was problematic since the administration had not made any public comments at all. Jordan warned: “I can see a real juicy lawsuit in the offing.” Clearly, UVA had influence over its branch college, because the next day, GMC Chancellor Thompson issued a statement that he was collecting all the facts before making a decision.

Figure 6. A letter from UVA’s office pushing for Thompson to respond to the Mallory House Incident and stating, “I can see a real juicy law-suit in the offing.” Jordan to Eisenberg correspondence, December 9, 1971. General Records (Office of the Assistant Provost), University of Virginia Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library, Box 3, Folder GMC “Mallory House Incident”: 1970.

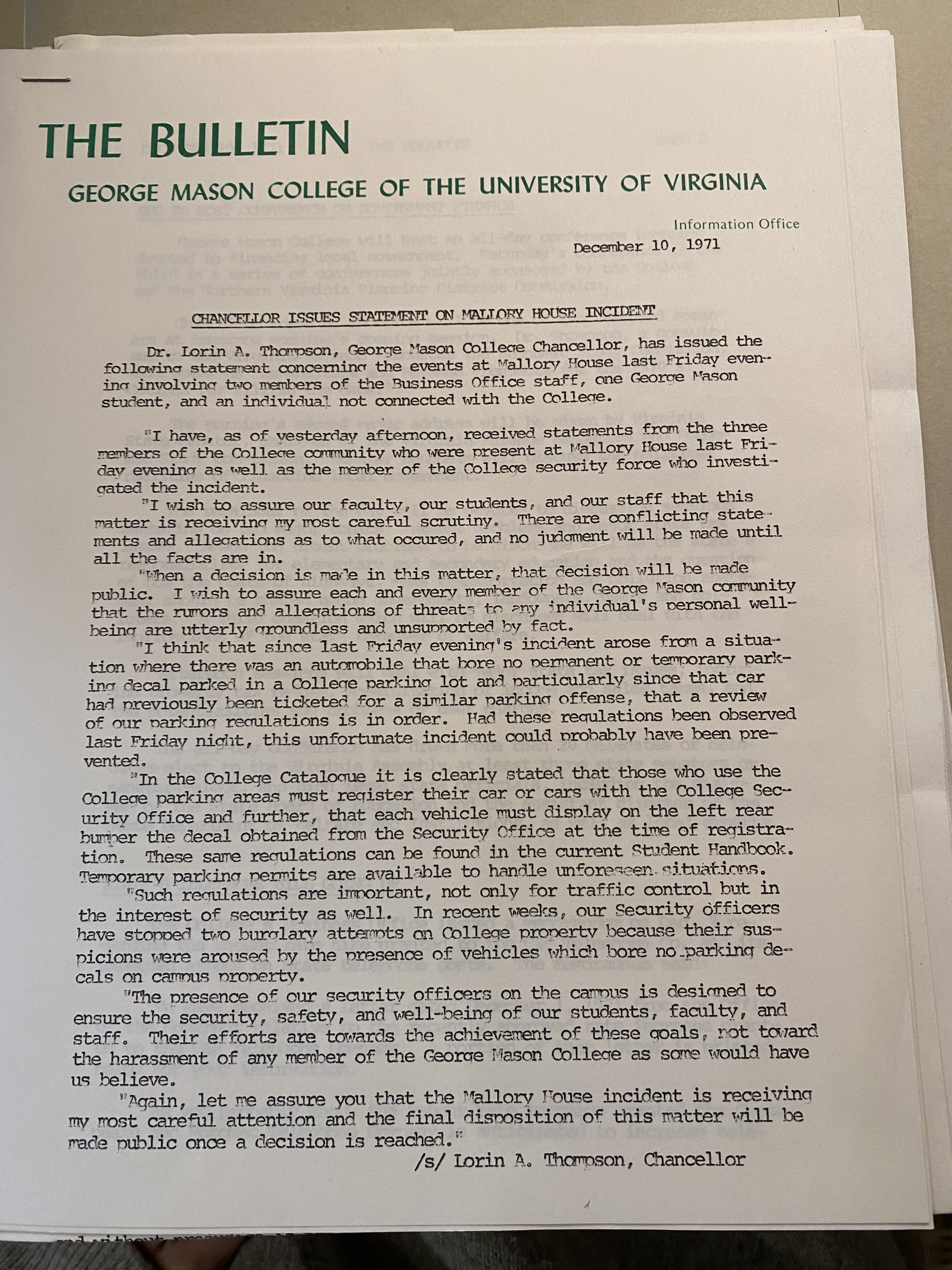

Student and administrative responses to the incident reveal campus issues over parking lots, regulations, and student safety. In his initial statement after the Mallory House incident, Thompson said, “had [university parking] regulations been observed last Friday night, this unfortunate incident could probably have been prevented.” Afterwards, students reportedly felt unsafe because the conflict involved a staff member rather than the issue over parking regulations. Student body president Jim Corrigan reported to a UVA representative, “To be quite frank, Mr. Conners’ temper is well known and as well, people are scared, students are scared, people are upset.” Corrigan, along with GMC’s General Faculty, recommended Conner receive administrative leave with pay. By the next semester, however, Thompson announced the case was closed as there was no solid evidence to move forward on any allegations.

Figure 7. The statement issued by GMC Chanceller Lorin Thompson December 10th, the day after UVA’s office called GMC to push for a statement. (“Chancellor Issues Statement on Mallory House Incident,” The Bulletin, George Mason College of the University of Virginia Information Office. General Records (Office of the Assistant Provost), University of Virginia Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library, Box 3, Folder GMC “Mallory House Incident”: 1970. December 9, 1971.

The Mallory House incident remained largely unresolved, but it illustrates the significance of campus parking lots as contested areas that witnessed moments of tension around who belonged and did not belong on campus. The Mallory House was a site bordering campus where staff parked alongside politically active students during a tumultuous time. As campus regulations became more enforced with tighter regulations, the lot became a greater site of conflict between staff and students. This event opens a window into the larger social and political issues Conner and Cassedy were both a part of, especially youth counterculture and abortion rights.

Laura Brannan Fretwell is a graduate research assistant at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media and a History PhD candidate at George Mason University. She researches race, gender, and memory in the American South.

Suggested citation

Please use the following as a suggested citation:

Laura Brannan Fretwell, "Parking Lots and Protests: The Mallory House Incident in 1971," Mapping the University, Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, George Mason University (2022): <https://mappingtheuniversity.rrchnm.org/narratives/mallory-house/>.

Broadside Dec 6, 1971. ↩︎

Clark statement. George Mason College General Records (Office of the Assistant Provost), University of Virginia Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library, Box 3, Folder GMC “Mallory House Incident”: 1970. December 8, 1971. ↩︎

Cassedy statement. George Mason College General Records (Office of the Assistant Provost), University of Virginia Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library, Box 3, Folder GMC “Mallory House Incident”: 1970. December 9, 1971. ↩︎

Clark statement. ↩︎