A Legacy of Student Protest at George Mason University

George Mason University was named in honor of one of the founding fathers of the United States, George Mason. Mason is well known for a variety of contributions to the foundation of this country. One of the outstanding ones was his refusal to ratify the constitution until a Bill of Rights was passed. This, in the mind of many experts and historians, was a protest for individual freedoms. Mason faculty and students have continued this legacy of protest since the University was created. Students and staff have protested on a variety of topics ranging from issues with university presidents to injustices around the globe. Protesting is an integral part of the university’s DNA. In fact, protests were conducted even before George Mason was accredited as a university.

When George Mason was still just a branch college of the University of Virginia there were protests in 1965 against Dr. Robert Reid, who was at the time the college’s director. His roles also included serving as Dean of the College, Dean of Students, Director of Admissions, and Business Manager. Dr. Reid was at the time the face of the university. However, his relationship with the students and the staff was rocky, to say the least. Beginning in the spring semester of 1965, the tension between Dr. Reid, faculty, and students was coming to a head. Faculty had observed Dr. Reid’s actions that semester and felt he was the wrong person to lead the job. They went down to Charlottesville to protest Reid’s leadership and plead for change to UVA’s chancellor, Joseph Vaughn, in person.

In their meeting with Vaughn, the Mason faculty brought forward several complaints about why Reid was not fit for the job. Their complaints included Reid’s lack of attendance in meetings, a new institutional dress code policy, and his lack of trust that the students and faculty would adhere to the university’s honor code. University of Virginia President Edgar F. Shannon tried to mediate between the two parties to resolve the issue. However, he was not successful and the faculty was forced to escalate the situation even further. Two events in May would result in the culmination of the issue. First, fifteen faculty members signed a petition resulting in a vote of no confidence.1 Two weeks after the petition was signed, six faculty members then filed their resignations.2 The University of Virginia’s administration continued to support Dr. Reid as the man in charge. However, he eventually gave them his resignation the following year. In doing so, he cited, “the Commonwealth of Virginia’s reluctance in granting George Mason independence from the University of Virginia.”[^3] Even though the faculty was not initially successful in their goal of removing Dr. Reid from his position, they incited change at the university and were willing to put their jobs on the line to do it.

[^3] “The Faculty and Student Revolt of 1965,” A History of Mason, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries.

Oral History interview with University President Robert Krug. Interviewed by Katja Hering, October 20, 2005.

Figure 1. Board of Visitors minutes detailing the resignation of six Mason faculty members. Board of Visitors Records, Special Collections Research Center, George Mason University Libraries, Box 1, Folder 6, Page 3, May 23, 1965.

A few years later in 1967, a Mason philosophy professor, Dr. James M. Shea, was also willing to put his job on the line for what he believed in. Dr. Shea was a believer in non-violence and encouraged his students to think critically about their leaders whether they were the ones in D.C. or the ones on campus. He helped to organize many protests on campus, often on the quad, and encouraged students to be politically active. All of this was occurring with the Vietnam War in the background. As the war progressed, Dr. Shea became more outspoken about his views. In particular his issue with the Selective Service and how it didn’t consider that some like himself lived a non-violent lifestyle. Dr. Shea eventually was selected to report for service but after refusing to take the oath to join he became more outspoken with actions of civil disobedience.

Many times this put him in the hot seat with the university with many thinking he should be removed from teaching. There were two acts of civil disobedience that occurred on school grounds that Robert Krug, then Dean, revealed in an oral interview. Krug cited Dr. Shea’s course material changing from Plato’s Republic to Man Child and the Promised Land, a textbook which coincided more with Shea’s personal beliefs. Additionally, Shea changed his grading system in class to be more self-reflective, which was also disapproved of by Krug.3 Shea himself believed this was one of the reasons his contract wasn’t renewed. Shea wrote in a letter to the school’s chancellor stating, “Dean Krug informed me in conversation on June 2, 1969, that his decision to recommend that my contract not be renewed was based ’ninety-nine percent’ on my grading practice (and one percent on the ‘fact’ that I ‘use students’ to “advance” ideas I believe in).”4 Shea felt that the university was targeting him based on his unpopular at the time political opinions.

However, Krug believed that it was the crimes Shea was accused and convicted of committing that explained why Shea’s contract was not renewed in 1970.5 Those crimes consisted of helping aid a draft dodger escape the country via a stolen automobile and a tax law violation. Dr. Shea’s actions disrupted the normalcy of the campus at the time. Shea decided it was worth more for him to stand up for what he believed in than to follow the rules. His choices paved the way for many students and faculty to feel more empowered to protest and stand up for what they believed in.

Oral History interview with University President Robert Krug. Interviewed by Katja Hering, October 20, 2005.

Figure 2. Photo of James M. Shea, a Mason philosophy professor who led protests during the Vietnam War. The Gunston Ledger, October 26, 1967. SCRC Digital Exhibitions, accessed June 30, 2022.

Figure 3. The first page of a letter written by Professor James Shea to Mason Chancellor Lorin Thompson discussing the university’s decision to not renew his contract. University of Virginia Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library, George Mason College General Records (Office of the Assistant Provost), Box 5, Shea File, June 24, 1969.

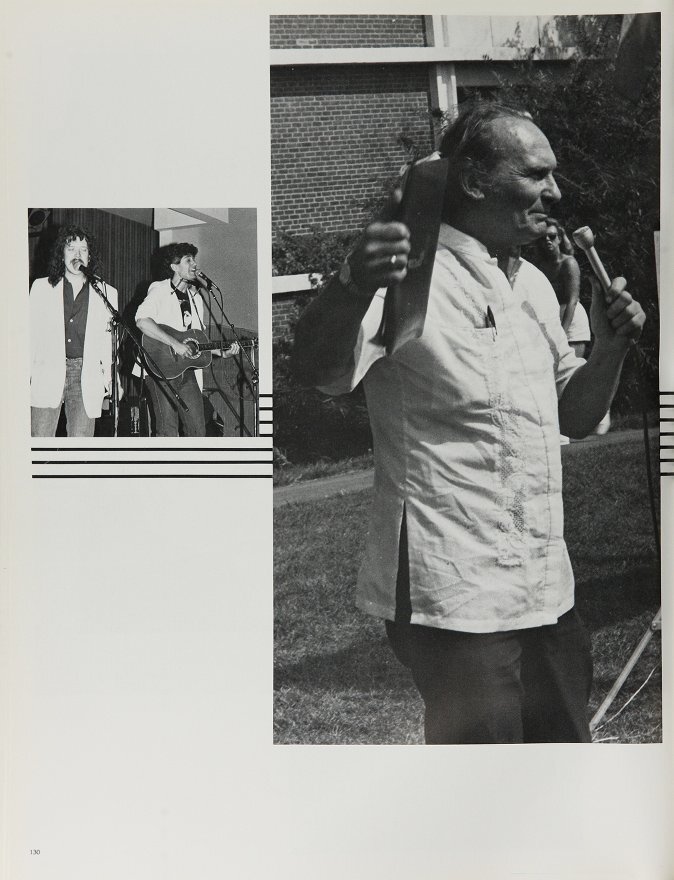

Since Dr. Shea’s time, fellow Mason professors and students have continued to protest for what they believe in. Various organized protests have occurred on George Mason campuses for local and worldwide efforts. There is photographic evidence from the 1987 yearbook that there were protests that coincided with popular movements at the time, specifically Rock Against Racism and Fast for Life. Both protests spoke to worldwide issues that also tied to home. Rock Against Racism was a movement which originated in the United Kingdom following public acts of racism and xenophobia. Fast for Life was a nuclear disarmament movement. Both movements had global implications and protests on George Mason’s campus showcase how protesting can be a global activity.

Figure 4. Students sitting on the quad participating in a sit-in style protest against U.S. aid to Contra forces during the 80s. By George! Yearbook, page 131, 1987.

Figure 5. Protest leader on George Mason’s Fairfax campus. By George! Yearbook, page 130, 1987.

However, protests on George Mason campuses in recent years have been directed more towards national issues or issues on campus itself. Some of the most notable protests in recent years include memorials for victims of police brutality, campus cleaning staff advocating for better working conditions, and protests against a Supreme Court Justice leading a summer study abroad course. These protested issues showcase the wide breadth of topics that are important to the George Mason University community. The university’s community in recent years has rapidly become one of the most diverse in the country. This newfound perspective has helped open the eyes of many in the community to injustices on campus, in the United States, and worldwide. Together the community will continue to advocate for a better world following in the footsteps of those Patriots who came before them.

Joseph Moore is an undergraduate history student and member of the class of 2023 at George Mason University who has lived in Fairfax his whole life. In addition to history, he is also studying film, media, and communication at GMU.

The Gunston Ledger, Volume 2, Number 10, May 25, 1965. ↩︎

Oral History Interview with Robert Krug, Special Collections Research Center (SCRC), George Mason University Libraries, 2005. Board of Visitors Records, Special Collections Research Center (SCRC), George Mason University Libraries, Box 1, Folder 6, May 13, 1981. ↩︎

Oral History Interview with Robert Krug, Special Collections Research Center (SCRC), George Mason University Libraries, 2005. ↩︎

James Shea Letter, University of Virginia Albert & Shirley Small Special Collections Library, George Mason College General Records (Office of the Assistant Provost), Box 5, Shea File, Jun 24, 1969. ↩︎

Oral History Interview with Robert Krug, Special Collections Research Center (SCRC), George Mason University Libraries, 2005. ↩︎